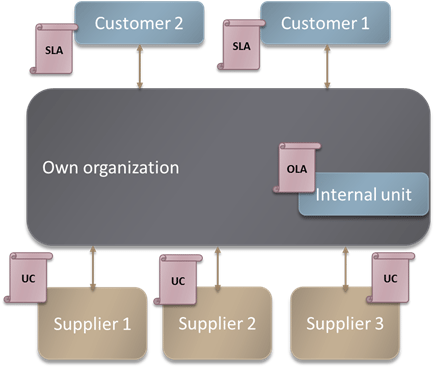

I can’t declare myself to be a fan of contracts and other forms of written agreements. That doesn’t mean that I am against the idea of their existence. As most of you do, so do I have many other issues to resolve and legally written documents are overhead, and therefore not in my domain. In the beginning (of my career) I only knew about the Service Level Agreement (SLA). But, later on, I found out that there are some other agreements as well, depending on which side you are looking at (see the figure). Essentially, ITIL and ISO 20000 don’t set much difference in the definition and purpose of the agreements, but the naming is a bit different.

Depending on your business, there can be many agreements in use. Below I will explain the three most common types of agreements.

Service Level Agreement (SLA)

Here’s a very common situation: you have a customer who is a user (or, better to say – buyer) of your service(s), you enter into an agreement with him and you define your relationship. The SLA is the result and the correct way to do it. That will be the written document that explains your relationship – service targets and responsibilities of both sides. It is an official document (meaning, it can be used in legal proceedings) written in legal language.

The SLA is usually defined by the Service Level Manager and checked (on legal issues) by the legal department. When signed by both sides, it sets targets that need to be achieved. It’s two sides of the same coin. On one side, if targets defined in the SLA (usually referred to as “service level targets”) are achieved, support for the services will be billed. But, on the other side, the SLA defines penalties for not achieving service level targets, e.g. priority 2 incidents must be resolved within 4 hours, and not achieving those targets activates penalties of a certain amount of money (or percentage of the monthly fee).

ITIL defines SLA in the scope of the Service Level Management process, and ISO 20000 defines SLA as a mandatory requirement as one of the Service Delivery processes.

Operational Level Agreement (OLA)

This is an agreement between you (a service provider) and another part of the same organization. It’s not a legally binding contract (i.e. not written in legal language) but an agreement because it’s inside the same organization. I experienced that organizations are defining relationships and obligations internally through agreements, but they are usually named “SLA.”

Since it is an internal document, legal language is used only to keep the form of the document (i.e., so that it looks like an agreement), but content is focused on defining the service that is provided, e.g., the facilities department gives support for datacenter air conditioning. The important thing is that the OLA must underpin the SLA. This means that, for example, if you are using a database administrator from another organizational unit and you have a SLA that says that database-related incidents must be resolved within 4 hours (for priority 2 incidents), then the OLA must have at least the same parameters for such incidents, or, I would suggest, even better (e.g., 3 hours).

OLA, as a name for the document, is used in ITIL. ISO 20000 does not explicitly name such an agreement, but there is a requirement that defines a situation when service components are provided by an internal group. For such cases, there shall be developed, agreed, reviewed and maintained a documented agreement to define activities and interfaces between the parties.

Underpinning contract (UC)

Well, I can’t remember ever seeing a document with such a name. Most probably, you have many such agreements, but you name them “SLA.” To avoid confusion – a UC is a contract that you have with your supplier, i.e., external parties who need to achieve service targets for you, but for them you are a customer. What does an organization sign with the customer? A SLA. Maybe you are a service integrator and you have external companies that provide you with hardware, software or some service. As mentioned regarding the OLA, the UC must also support SLA parameters, and you use the UC to ensure that you get what is expected for the money you pay to the external company.

ITIL and ISO 20000 define the process and document (i.e., agreement) that is used, but the naming is different. The UC comes from, and is used by, ITIL, while ISO 20000 defines that the contract shall be agreed upon without defining a particular name for it.

Usage and relationship

Let me get back to the beginning. As I said, I’m not a fan of written contracts, but I think that they are necessary. As a matter of fact, they will make your life easier because they will define who should do what, and when, and how much it should cost…and many other things. In short – they will “clarify the rules of the game.” But, there is one more thing: leave them in the drawer until there is nothing else that can solve the conflict. But, be careful; being a successful service provider means having (and maintaining) good relationships on all sides. A situation where agreements are judging can imply that the relationship is in danger. Energy and time used in clarifying what the SLA says can be better utilized in maintaining a relationship with the other party.

Look here for a free preview of SLA, OLA and UC templates.

Neven Zitek

Neven Zitek