Now that the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is in force, it’s time to see if the aim of European legislators to create a technologically neutral regulation about data protection has been achieved. The first test is with blockchain technology, which is (among other things) a completely brand-new way to collect, process and store data (even personal data).

Firstly, what is blockchain?

Blockchain is one of the so-called “distributed ledger” technologies. This technology provides high security standards for transactions because only an authorised user (with its own private cryptographic key) can register information on ledgers, affording the rights given by the administrator of the blockchain.

It can be structured in one of two ways: one allows for anyone participating in the blockchain to read or implement it (the so-called “public blockchain”, i.e. Bitcoin), while the other only allows some users with certain permission levels to write on the blockchain or insert nodes (permissioned blockchain) in the private blockchain. Of course, some in-between forms can be structured as well.

Once the information has been registered, all the other users participating in the blockchain know about it, and such information is stored simultaneously on every distributed ledger. Each transcription on a ledger immediately modifies all of the distributed ledgers, while cryptography and time stamps protect from alteration and modification.

If it is a safe technology, why should you be concerned about the GDPR?

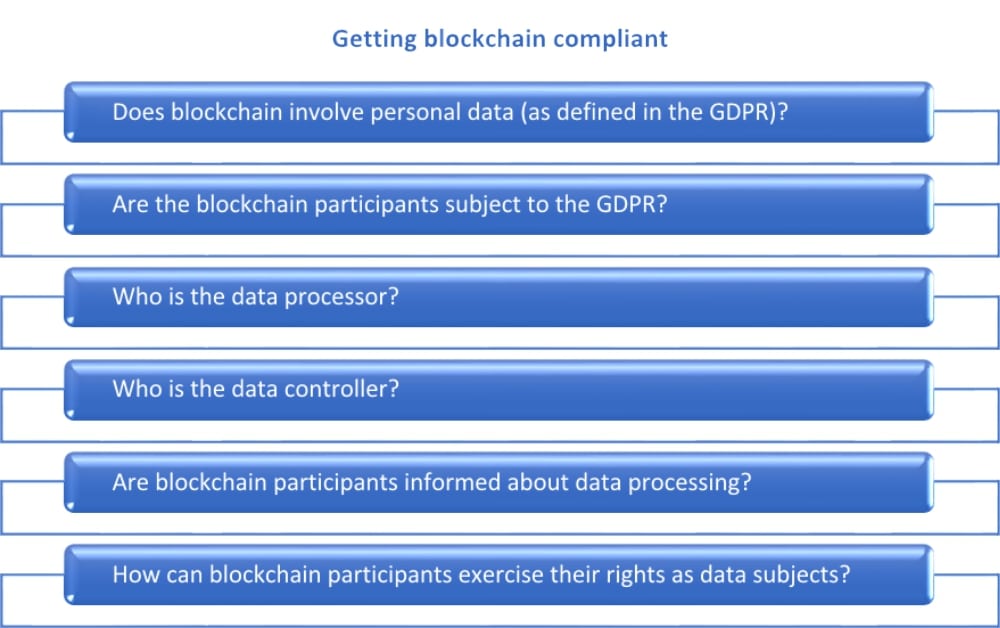

But, is blockchain GDPR-compliant? Well, being a safe technology does not immediately mean that this technology is GDPR-compliant. Here are some things to be checked:

While the first two points indicate whether the GDPR is applicable or not, the other points highlight some critical aspects of GDPR compliance of the blockchain.

Personal data, and how does blockchain protect privacy?

The GDPR defines personal data in Art. 4 n. 1 as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’)”; therefore, if the transaction in the blockchain involves personal data, such data will be processed according to the GDPR.

The GDPR applies to data processors or data controllers who are established in the European Union (regardless of whether the processing takes place in the Union or not), or who offer services to data subjects in the European Union (regardless of whether the processor is established in the Union or not), or the monitoring of data subjects’ behaviour inside the territory of the Union.

Such broad application means that if a transaction made through the blockchain involves personal data (i.e. the names of legal representatives of the companies) inside the Union, or involves services in the Union, or monitors data subjects’ behaviour inside the Union (i.e. from shopping preferences to health devices), in each of these cases, the GDPR will apply.

To learn more about personal data transfers, read the article 3 steps for data transfers according to GDPR.

Data controller in blockchain

Ok, then. If the GDPR applies, then who is the data controller in a distributed ledger technology such as blockchain? Some commentators have stated that the model of data processing illustrated in the GDPR reflects a traditional and centric structure. In fact, in reading the GDPR, we can notice that it is: the data controller collects, processes and stores data (centric), and the data processors can always exercise control over the collected data; that’s why the data subjects can always refer to the data processor to exercise their rights, because the data processor is the only person who has control over the collected data.

On the contrary, the blockchain distributes data through ledgers in order to share knowledge and control of that data, so no entity has exclusive control over the processed data. Because of this different structure (central data processing vs distributed processing), some commentators stated that blockchain cannot be compliant with the GDPR because of its distributed structure, which makes impossible to identify the data processor; others highlighted the technological neutrality of the GDPR structure and emphasise every element that can make the blockchain compliant again.

Among these commentators, some argued that Article 26 of the GDPR allows “joint controllers”, “where two or more controllers jointly determine the purposes and means of processing”. So, permissioned blockchain could fit in the definition because while the ledgers are distributed, only a few users will have the power to insert nodes and add transactions. Permissioned users will be joint controllers of data processed in the blockchain, sharing the purposes and means of processing.

For more about the responsibilities of data controllers, read the article The Obligations of Controllers Towards Data Protection Authorities According to GDPR.

Data subjects in blockchain

Data subjects involved in the blockchain will be informed with a privacy notice about data processing through the blockchain, because such choice has an impact on the rights they can exercise. The GDPR allows data subjects to exercise these rights:

- the right to access to data processed (Art. 15);

- the right to rectification of data processed (Art. 16);

- the right of erasure or “right to be forgotten” (Art. 17);

- the right to restriction of processing (Art. 18);

- the right to data portability (Art. 20);

- the right to object to data processing (Art. 21);

- the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing (Art. 22).

The structure of blockchain requires that each piece of information added to the blockchain cannot be modified or removed and it can be controlled by all the participants in the blockchain.

So, how can data subjects exercise their rights? There is not a true answer to this question, as the GDPR has only been in effect for one year, and authorities and commentators are solving problems as they arise.

Some commentators suggested anonymising personal data (so that the GDPR is no longer applicable), while others suggested the destruction of the keys associated with personal data so that they are stored on the blockchain, yet no longer legible (so, basically erased). These solutions might work on private and permissioned blockchains, but they cannot work on the public blockchain because of the costs associated with modifying the entire set of distributed records.

To learn more about the Privacy Notice, enrol in this free webinar: Privacy Notices under the EU GDPR.

The future of blockchain

In conclusion, we can say that the impact of the GDPR on blockchain requires operators to design blockchain structure while paying attention to data processing (according to the privacy by design principle), to provide notice to data subjects about the blockchain structure and its impact on the exercise of their rights, and to minimise the personal data being processed. All these elements are the fundamental elements of the GDPR and can be transposed in the blockchain. More solutions will come through technology, commentators and authorities’ suggestions.

The European Commission is working on blockchain because they recognise its huge potential impact on administrations, businesses and the society in general, and because of its part in the Digital Market Strategy as it relates to the GDPR.

To learn more about how to help any business comply with the GDPR (including blockchain), enrol in this free online training: EU GDPR Foundations Course.

Alessandra Nistico

Alessandra Nistico